Stop Trusting Devices. Start Controlling Them. An Introduction to udev.

In the last few posts, we have been asking uncomfortable but necessary questions.

Where did my disk space go?

Why is this system slow right now?

What is listening on the network?

Now it is time to ask a question most administrators never ask until it hurts. Why does this system trust whatever gets plugged into it?

On a default Linux system, hardware shows up, gets named, gets permissions, and becomes usable with very little scrutiny. That is not magic. That is udev making decisions on your behalf.

If you do not define those decisions, the system does.

What udev Actually Is

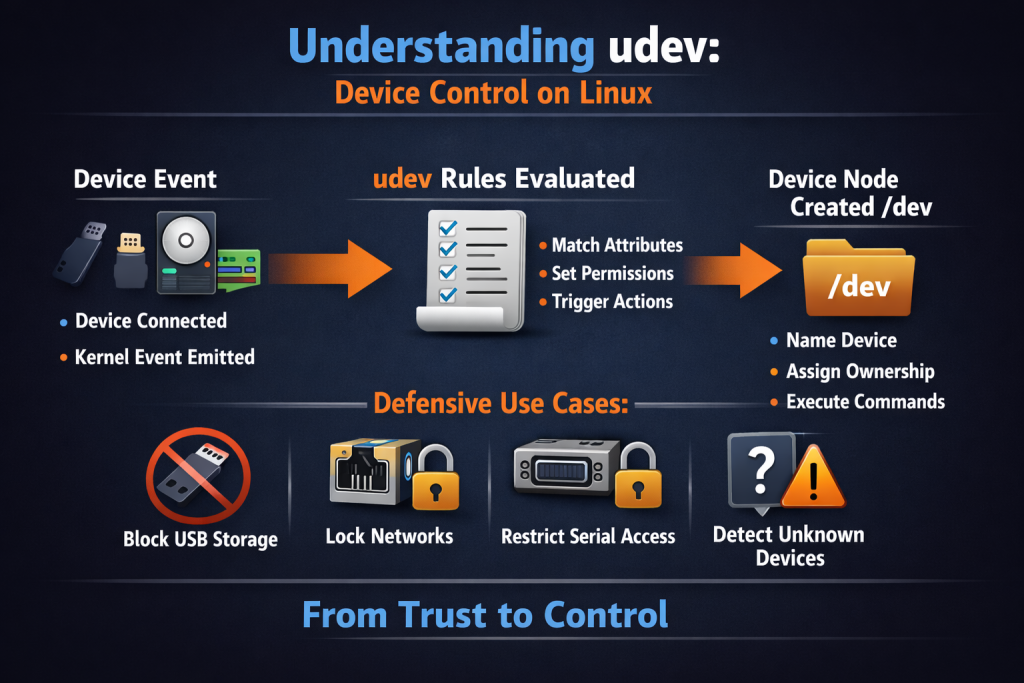

udev is the user space device manager for Linux. It listens for events from the kernel and decides what to do when hardware appears, disappears, or changes state.

Every time you plug in a USB device, attach a disk, add a network interface, or expose a serial port, udev evaluates rules and acts. Those actions include:

- Creating device nodes under /dev.

- Naming devices.

- Assigning ownership and permissions.

- Triggering additional commands or services.

This is not cosmetic. This is control.

The Problem udev Solves

Linux does not promise stable device names.

The disk that appears as /dev/sda today may be /dev/sdb tomorrow. USB adapters change ordering. Virtual devices come and go. If you rely on raw device names, you are building systems that fail quietly and unpredictably.

udev exists to solve this by matching devices based on attributes that actually describe what the device is, not the order it happened to appear.

More importantly, udev is the first policy gate between hardware and user space.

How udev Works, Without the Mystery

The flow is simple.

The kernel detects a device. The kernel emits an event.

udev receives the event. udev evaluates rules in order. Actions are applied.

That is it. No daemon polling hardware. No guessing. Pure event driven control.

Once you understand this flow, udev stops being intimidating and starts being useful.

Anatomy of a udev Rule

A udev rule has 2 parts.

- Match conditions.

- Actions.

Match conditions answer, “Is this the device I care about?”

Actions answer, “What should I do if it is?”

A minimal example looks like this conceptually: Match a USB device by vendor and product ID. Assign restrictive permissions. Optionally trigger logging.

You are not naming devices by hope. You are naming them by identity.

Why This Matters for Defense

Most administrators think of udev like plumbing. That is a mistake. No, udev is enforcement.

Here are practical, defensive use cases that matter in real environments.

Lock Down USB Storage by Default

Removable media remains a common intrusion vector. Malware does not care how boring the entry point is. With udev, you can:

- Identify USB mass storage devices.

- Set permissions to root only.

- Prevent automatic mounting.

- Log every insertion event.

This turns “someone plugged something in” into a controlled, observable action.

Enforce Predictable Network Interface Naming

Network interfaces that change names break monitoring, firewall rules, and scripts. udev rules can bind an interface name to:

- MAC address.

- Device path.

- Hardware identifier.

You stop chasing interface renames and start enforcing consistency.

Restrict Serial and HID Access

Serial ports, USB keyboards, and HID devices are often overlooked. udev allows you to:

- Limit access to specific users or groups.

- Prevent unauthorized interaction with sensitive interfaces.

- Detect unexpected device classes.

This matters on servers, kiosks, and lab systems.

Detect and React to Unknown Devices

udev can trigger actions. That action does not need to be destructive. It can be visibility. Examples:

- Write to syslog when a new device class appears.

- Tag events for SIEM ingestion.

- Notify administrators that hardware has changed.

If you care about integrity, you should care about hardware state changes.

Observability Comes First

Before writing rules, observe. Linux gives you the tools to see exactly what udev sees.

Use udevadm monitor to watch events in real time. Use udevadm info to inspect device attributes.

This is reconnaissance, not configuration.

You do not write good rules by guessing. You write them by watching how the system actually behaves.

Where Rules Live and Why Order Matters

udev rules are processed in order. Later rules override earlier ones.

System rules live under /lib/udev/rules.d. Custom rules belong under /etc/udev/rules.d.

This separation matters. You do not edit vendor rules. You layer policy on top of them. Think of udev rules as firewall rules for hardware.

The Takeaway

udev is not optional. It is already running. The only question is whether it is enforcing your intent or default assumptions.

If you trust every device that appears, your system will too. If you define identity, permissions, and behavior explicitly, Linux gives you the hooks to enforce it.

This is not about paranoia. It is about control.

In the next post, we can move from introduction to practice. Real rules. Real examples. No theory.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.